Introduction

Trust is a key foundation of social cohesion. Trust is a basis for our involvement and engagement in society and our social wellbeing and connectedness. Trust is one of the most important and studied forms of social capital (e.g. Leigh, 2006) and is believed to be an important foundation for social, economic and civic engagement in society and is strongly associated with positive mental health and wellbeing (Nannestad, 2008).

Trust in society is multidimensional. Critical to social cohesion is the trust we have in other people in our communities and in the nation as a whole (interpersonal trust), as well as the trust we have in government, the political system and societal institutions (institutional trust). Interpersonal and institutional trust are separate but related concepts. Our experiences and perceptions of people in government and other institutions shapes how we view and trust people generally in society and vice versa (Kim & Kim, 2021).

Trust in government is important for democracy and the functioning, strength and legitimacy of our political system. Distrust can fuel disengagement and disaffiliation, especially among those who experience social, economic and political marginalisation in other areas. Distrust can also fuel discontent with the political system and the perceived political class, social and political polarisation and demands for fundamental change of either a democratic or anti-democratic character. Blind and unquestioning trust in government, however, is a risk to democracy, making political engagement and activism a critical ingredient in keeping governments accountable and maintaining the strength of our democracy.

In this chapter, we explore trust in Australian society in recent years, views on the strength of our democracy and how these attitudes and perceptions translate to political engagement and action. We conclude with a discussion of the critical inequalities in trust that weigh down our overall levels of social cohesion in Australia and that require community and public attention.

Trends in interpersonal and instutional trust

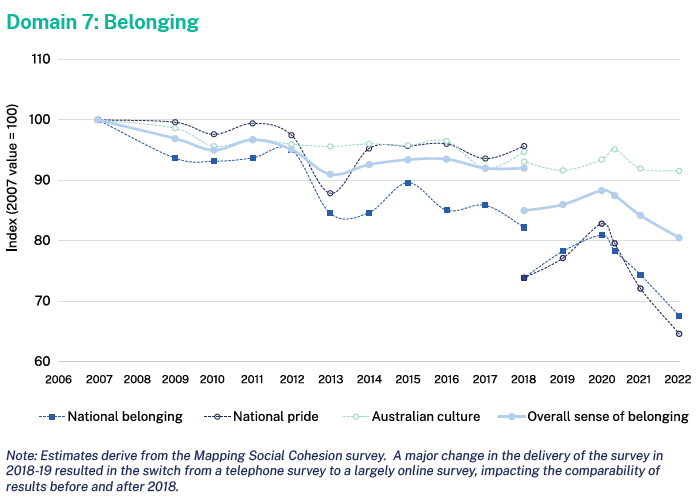

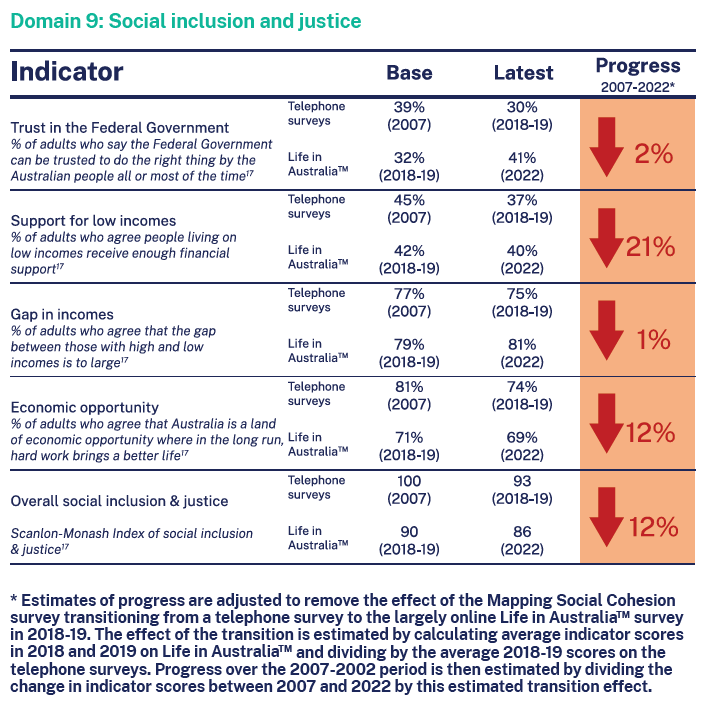

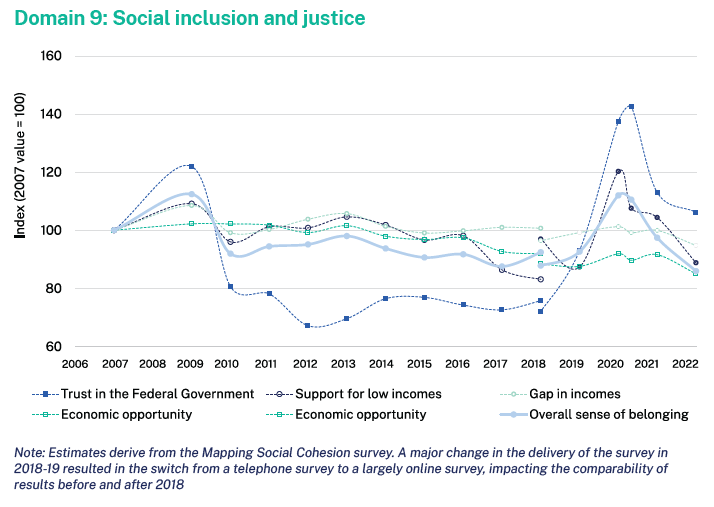

Levels of trust in Australian society have been mixed in recent years. Trust in the Federal Government was relatively low throughout the politically turbulent 2010s. Over the course of this decade, fewer than one-in-three adults believed the Federal Government could be trusted to do the right thing by the Australian people all or most of the time (O’Donnell, 2022). The Scanlon-Monash Index of Social Inclusion and Justice, which includes the measure of trust in the Federal Government, declined from a peak of 112 in 2009 to an average of 93 during the 2010s.

There was though, strong and widespread support for the way in which state and Federal Governments handled the COVID-19 pandemic. In fact, belief that the Federal Government can be trusted to do the right thing all or most of the time increased from 36 per cent in 2019 to 54 per cent in July 2020, not long after the first national lockdown. When asked specifically about COVID-19, approximately two-thirds of people in 2022 said that the Federal Government and their state or territory government had handled the pandemic fairly well or very well, a decline from the very high levels of approval in 2020 but still representing substantial majorities of the population.

Positive response to governments’ handling of the pandemic was reflected in several of our interviews with people who have migrated to Australia over the years. Many of those we spoke with experienced difficult times during the pandemic though most, nevertheless, appreciated government efforts to protect our health and wellbeing:

It felt quite different from [my home country] when COVID happened… The state was the one that was the most affected… And I was quite impressed at how the state can have so much control over each state. Because in [my home country] it’s just one government, and they have to rule the very country and it takes so much to change something… I felt quite good that each state had the decision to make. It was not amazing because we had to go through the hard lock down. But still, I feel like it’s good to have that power (Interview 1.2).

Trust in government and our leaders, however, remains on uncertain ground. Internationally, trust in the Australian national government is similar to, if not somewhat below, the average across developed countries of the OECD and substantially below countries such as Finland and Norway (OECD, 2023a). In 2022, the level of trust in the Federal Government remains above its longer-term average though has declined from its 2020 peak. In 2022, 41 per cent of people said the Federal Government could be trusted to do the right thing by the Australian people all or most of the time. One-quarter of people believe that government leaders in Australia abuse their power all or most the time, while 78 per cent believe this is the case at least some of the time. A degree of cynicism towards government was also reflected in some of our interviews:

Uh, its unpredictable. Election time is good. You hear good news and then everyone is giving [you a] flyer… But after the election, it’s different. And then they try to control the cost of living and then they say it and then the cost of living is up. The bills are up, gas is increased, petrol and electricity and everything is increased… When the group comes to power, the situation emotionally looks okay from the atmosphere, from the media. Then everything disappears… (Interview 1.17).

It just seems to me that they think about lining their own pockets before they actually try to make any changes and move towards something that makes sense. But you know, that’s just my opinion. It just seems they seem to spend a lot of money on campaigning about what they will do, and then not delivering on what they promised and trying to get out of it (Interview 3.4).

Australians are generally more trusting of other people, though we are near evenly split between those of us who are trusting and those who are not. In 2022, 49 per cent of people on the Mapping Social Cohesion survey believed that, generally speaking, most people can be trusted, leaving 50 per cent of us to say you cannot be too careful in dealing with people. Internationally, trust in others in Australia is close to the OECD average but well below the likes of Denmark, Finland and Norway (OECD, 2020). Encouragingly, interpersonal trust increased during the heights of COVID-19. The proportion of adults who agree that most people can be trusted increased from 43 per cent in 2019 to 49 per cent in July 2020 and 52 per cent in 2021 and remained at a reasonably high level in 2022.

In general, I find people to be very friendly. If you ask, people will be willing to give you the help you need… Whenever I needed critical help there’s always help that’s been given to me, and that is because people did not judge me for asking for help, and they took my help as it is, and they offered help, and I’m very thankful for that in the first place, and always will be (Interview 1.20).

Trust in society is an important foundation for engagement in a wide range of social, community and civic activities. Even after accounting for demographic and socioeconomic differences in the population, people who are trusting of others and the Federal Government are more likely to be involved in social or religious groups, including sports clubs, church, hobby, ethnic and adult education groups according to results from the Mapping Social Cohesion survey. People who are trusting of others are also more likely to be involved in community support groups like Rotary groups, the Smith Family, Save the Children, the Australian Red Cross and State Emergency Services.

Trust in democracy and the political system

Trust in the government of the day is, of course, infused with no small amount of partisan politics. Over and above such politics, there are critical questions as to the belief and confidence people have in Australian democracy and the system of government we have.

Results from the long-running Australian Election Study suggest that satisfaction with democracy, while volatile over the last five decades, has been generally declining since 2007 (Cameron & McAllister, 2022). The proportion of people who are satisfied with democracy declined from 86 per cent in 2007 to 59 per cent in 2019, before increasing again to 70 per cent in 2022. Likewise, the proportion of people who believe the government is run for a few big interests rather than all people increased from 38 per cent in 2007 to 56 per cent in 2019 and 54 per cent in 2022. Since 2007, people are also more likely to say that it does not matter who is in power and less likely to say that politicians know what ordinary people think.

Trust in government may also vary between different levels of the political system. While individuals may feel dissatisfaction with political decision-making or policy at the federal level, their views about the operation of the government at the state level or even at the municipal level may be quite different.

The state government and the council, they are amazing. They try their best to do what is best for their people, for the community… The federal government doesn’t give a lot of attention to Tasmania, unfortunately, although it’s a beautiful place. When there is an event we really attract a lot of tourists but there is not enough funds. That is why the council try their best to boost the community, to boost the state with new events, new functions and new festivals, just to lift up the economy and create new jobs (Interview 6.5).

Dissatisfaction leads many to support major and minor changes to our system of government. In the 2022 Mapping Social Cohesion survey, 36 per cent of people said the system of government in Australia requires major changes or needs to be replaced. A further 48 per cent believe minor changes are required, leaving just 14 per cent who believe the system works fine as is. The proportion of people believing that major change is required, declined during COVID-19 but returned to its longer-term average over the last ten years in 2022.

Support for systemic political change in Australia does not translate to support for an antidemocratic or authoritarian state. In the 2022 Mapping Social Cohesion survey, 51 per cent said that having a strong leader who did not have to bother with parliament and elections would be a very bad way of governing Australia, while a further 29 per cent said it would be fairly bad. If anything, the strength of this anti-authoritarian sentiment has strengthened over time and is high, regardless of whether or not people believe that major or minor changes are required to Australia’s system of government. Change therefore, is perhaps best achieved through more democracy than less.

Political trust among new Australians

Migrants to Australia have a diverse range of views about the Australian political system. On the one hand many appreciate the strength of political institutions and the opportunities afforded to them for participation, particularly in comparison to the systems and experiences of their countries of origin. On the Mapping Social Cohesion study, migrants have generally been more likely to trust the Federal Government including both those from English and non-English speaking backgrounds than people born in Australia (O’Donnell, 2022).

Well, you know, from someone who is coming from a post-Communist country in Middle Europe that was locked down for many years, I found Australia very liberal in terms of the services offered, and just the focus on people. (Interview 3.4).

Among those we spoke to, people who have migrated to Australia value everyone’s right to participate; the freedom to speak openly about political matters and to be critical, if necessary; consultative processes that allow input into political decision-making; a functioning opposition that can work as a counterpoint to the government in power; being able to institute a change in government and having a voice.

My overall opinion of Australian democracy is positive since it offers a forum for free speech, participation in society, and the defence of individual rights. But it has advantages and disadvantages, just like every other political system. As an [Asian] immigrant, I value the democratic discourse and participation opportunities provided by Australia (Interview 4.4 – written response).

I love how in Australia, sometimes the opposition or even the people can come up with ideas and propose those ideas and they can be heard. Whereas in other countries you have to be careful. So freedom of speech is something really good – a right that everyone should have. No one should be prosecuted or targeted just because they have their own opinion (Interview 3.11).

However, some interviewees also expressed dissatisfaction about how particular issues of concern to them are being responded to by the government, such as visa policy and discrimination, and concern about broader issues of representation and voice.

Does the government do the right thing by people from different cultural backgrounds? I don’t think it’s necessarily black and white. I think in certain instances they [the government] have done the right thing by people. And I think in certain instances they’ve done the wrong thing by people. And for the most part, I think, where they’ve done the wrong thing by people from different cultures and communities is around election time when they are looking for the votes from the majority. And then, I think once they establish some level of power they cool off on some of those statements. But a lot of the time, by then, the damage has already been done (Interview 4.2).

Political participation

Participation in politics and the democratic system is an important behavioural manifestation of institutional trust. Participation can take a number of forms, including voting, signing petitions, joining protests and boycotts and communicating with Members of Parliament.

But people here are a lot more engaged in the politics as well, which is a great thing. I think everyone seems to have certain opinions of the government, good or bad. They feel a lot more educated – they educate themselves by actively watching the news, reading articles, being more conscious about discrimination or the First Nations issue… People do have a voice here, even people within my generation, the younger generation. And obviously the government is very aware of that (Interview 1.5).

Voting is, of course, one of the foundational acts of political engagement. Voting rates are very high in Australia by international comparison with voting compulsory for eligible populations. There is a reasonable degree of variation though in voting practices in Australia that speak to levels of engagement in democracy and the political process.

Here, either you like it or not but you’ll vote or be fined. Which I guess is a really good thing if we look at it. For the government to enforce it, [to make] you exercise your rights as a citizen to be able to choose your government, then if they’re not performing well you can hold them to account. I think it’s a really good thing. The ability for the people to either put you there or remove you, it just stops them from getting too much over their heads. It lets them know there’s a limit to how far they can go and reminds them that they are actually representing the people that put them there (Interview 1.7).

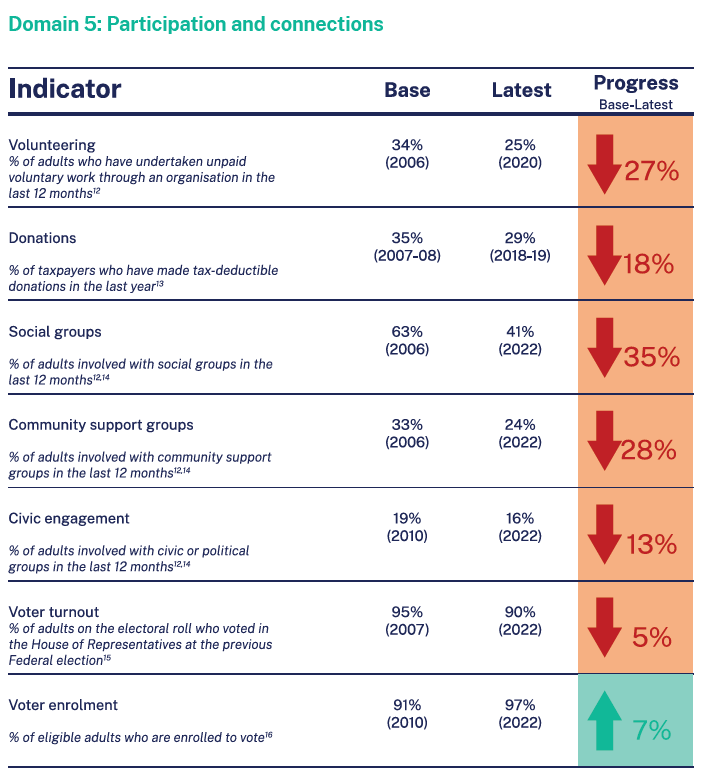

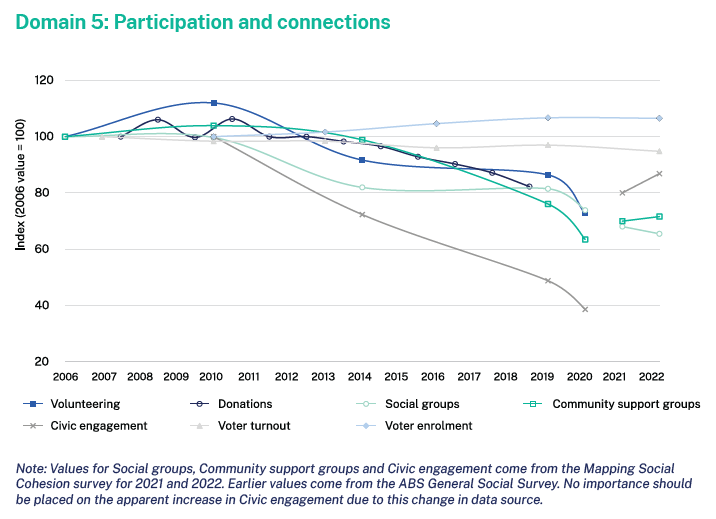

The Australian Cohesion Index measures the extent of voter turnout in the social and community participation domain with data derived from the Australian Electoral Commission (AEC, 2022). Voter turnout – or the number of votes cast as a proportion of the number of people enrolled to vote – was 90 per cent in 2022 for both the House of Representatives and the Senate. This turnout was five points lower than what it was in 2007 and the lowest level in several decades. While this might be a cause for concern, the low turnout in 2022 was likely the result of very high voter enrolment. The number of eligible people who were not enrolled to vote declined from 1.4 million people in 2010 to 564,000 in 2022 (AEC, 2023a). Overall, approximately 88 per cent of the eligible population voted in the 2022 Federal election, similar to levels since 2013 and higher than the 2010 election (85 per cent). Informal voting, for its part, has remained in line with its 2007-2022 average (AEC, 2023b).

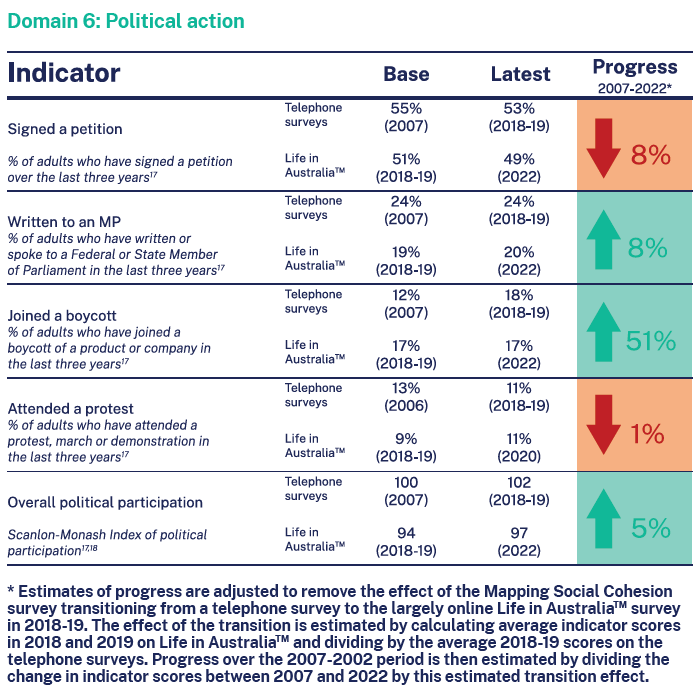

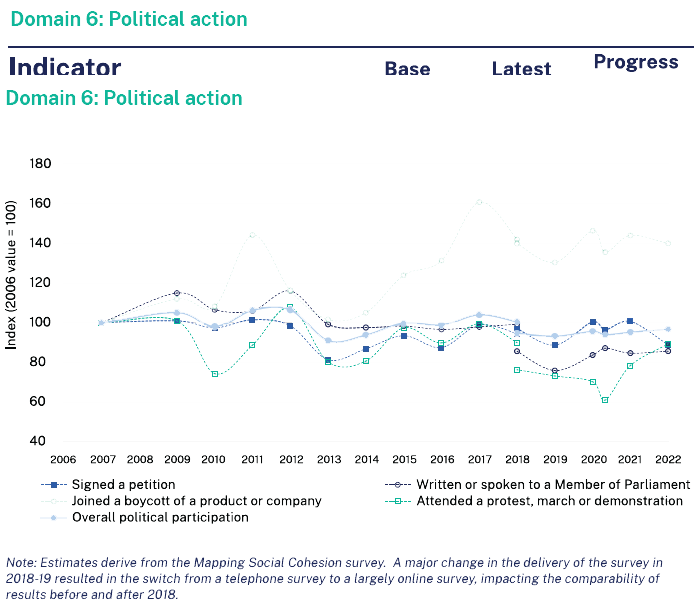

Political participation has otherwise been reasonably stable in recent years with modest fluctuations. In the Mapping Social Cohesion study, the index of political participation has moved within a relatively narrow band between 90 and 110 between 2007 and 2022. In the more recent period between 2018 and 2022, 50-60 per cent of people say they have signed a petition in the previous three years, one-in-five people consistently report having written or spoken to a member of parliament, one-in-six people have joined a boycott, one-in-ten people report attending a protest, march or demonstration and one-quarter posted or shared political information or views online.

Political participation has changed in composition in recent decades with the rise in digital technologies. According to the Australia Election Study, the proportion of people who had contacted officials in person or in writing in the previous five years declined from 27 per cent in 2001 to 16 per cent in 2022, while the proportion who had contacted officials by email increased from 13 per cent in 2010 to 23 per cent in 2022 (Cameron & McAllister, 2022). The proportion who had signed a written petition declined from 72 cent in 1987 to 32 per cent in 2022, while the proportion who had signed an online petition increased from 12 per cent in 2004 to 48 per cent in 2022.

Trust and participation

Political participation has an interesting and complex relationship with institutional trust. On the one hand, political protests and other forms of political activism arise from disenchantment with current policies and systems. By the same token, activism signifies a willingness to engage and fight for change, and perhaps also a belief that our leaders will respond and change can be achieved.

The Mapping Social Cohesion survey generally suggests that people are more politically active if they distrust government and the political system. However, the complexity of the relationship is reflected in the diversity of responses. In 2022, 72 per cent of people who almost never trust the Federal Government and 69 per cent who think Australia’s political system needs major change said they had signed a petition, communicated with a Member of Parliament, joined a boycott or protest or posted about politics online in the last three years. While these proportions are significantly higher than for people who are more trusting, the majority of people who trust the government most of the time (57 per cent) or believe the political system needs only minor change (59 per cent) had also been politically active in these ways. Political engagement therefore is an important means of effecting political change for people with both high and low confidence in the current system.

Political participation is no doubt associated with political knowledge. Full and meaningful participation relies on having an understanding of the system you are engaging with and knowledge of potential avenues of participation. For migrants to Australia, the Australian political system is complex, with three independent (yet sometimes interconnected) tiers of government. Processes are in place for proving political information and education, particularly around the time of citizenship, but it is limited. The agency of individuals or cultural community groups sometimes helps to fill this void.

We know the problems; we understand the needs. But our community sometimes doesn’t understand how the system works. That’s where we are in the middle. We are in between, you know, the systems here ourselves with the services and stuff and then with our communities (Interview 3.10).

The system of government is hard to understand. The men understand it, it is not easy for women (Interview 1.8).

Inequalities in trust

Differences in trust across society mirror socioeconomic inequalities. As noted in the Mapping Social Cohesion 2022 report, people with lower levels of education, those living in disadvantaged neighbourhoods and those who describe themselves as poor or struggling to pay their bills are much less likely to believe that people can be trusted. In 2022, just 28 per cent of people who were struggling to pay bills or poor were trusting of other people, compared with 68 per cent for people who describe themselves as prosperous or very comfortable and 53 per cent for those who are reasonably comfortable. Only one-in-five people (20 per cent) who said they were struggling to pay bills or poor in 2022 believed the Federal Government could be trusted all or most of the time. The way in which financial pressures breed cynicism and distrust in the political system was reflected in some of our interviews:

People can’t even afford basic necessities like electricity – it’s just gone through the roof, you know? So trust in the government I think is not there at the moment… I feel like for the first time ever they’ve just lied and lied and lied. I never used to think that about the Australian government before. Yeah, politics is a bit of lying, but it’s just been so full on in the last two to three years that people don’t trust them anymore (Interview 3.1).

Young adults also, report lower levels of trust. In 2022, 42 per cent of 18-24 year-olds and 46 per cent of 25-34 year-olds believe that people can be generally trusted, compared with 54 per cent of those aged 65 years and over. Just 36 per cent of 18-24 year-olds and 32 per cent of 25-34 year-olds believed the Federal Government can be trusted to do the right thing all or most of the time, compared with 48 per cent of people aged 65 years and over.

Demographic and socioeconomic gaps in interpersonal trust appear to have widened in recent years. Between 2018 and 2022, a reasonably steady 28-30 per cent of those struggling to pay bills were trusting of others. Levels of interpersonal trust increased substantially, by contrast, for people who describe themselves as prosperous or very comfortable (54 per cent in 2018 and 68 per cent in 2022) or reasonably comfortable (45 per cent in 2018 to 53 per cent in 2022). Similar patterns were recorded across age groups, where levels of interpersonal increased for people aged 35 years and over between 2018 and 2022 but remained stable for those aged 18-34 years. The tends to suggest that the galvanising effect of our public and community response to COVID-19 was not felt by all, leaving some groups, particularly young adults and those who continue to struggle financially, feeling marginalised.

Differences in trust across age and socioeconomic groups are common around the world. Young adults aged 18-29 years were less likely to trust other people than those aged 50 years and over in all 14 developed countries surveyed in the Pew Research Centre’s 2020 Global Attitudes Survey, with significant differences recorded in nine of those 14 countries (Connaughton, 2020). Among these countries stretching across western Europe, north America, east Asia and Australia, Australia recorded the second largest gap in trust between young and older people. More encouragingly though, the gaps in trust in Australia between high and low income and education groups were smaller than most other surveyed countries.

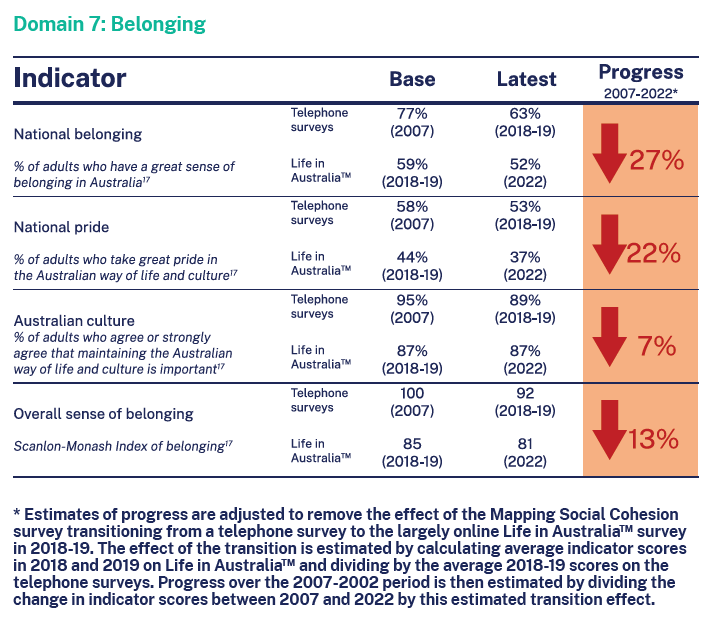

Inequalities in trust across society illustrate the multidimensional pressures on social cohesion in Australia. As explained in this chapter, trust in people and government is far from a universal trait across the country, nor in the world. Approximately as many people are distrusting of others as are trusting, while a minority of people consistently trust the Federal Government. Perceptions of our democratic system nevertheless remain strong and most calls for change are likely in the direction of strengthening rather than weakening democracy. Our sense of trust was also strengthened during the COVID-19 pandemic, giving governments an important tool to protect our health and material wellbeing. We can hope to learn from the pandemic and restore that trust. A key first step is to identify and address inequalities in trust across demographic and socioeconomic groups.

Expert Commentary by Danielle Wood

Written by Danielle Wood

Chief Executive Officer, Grattan Institute

‘Ultimately, trust is the political capital that our leaders draw on to make hard policy decisions. And building this capital is crucial for supporting the necessary actions on big, but slow-moving, challenges such as climate change and population ageing.’

The Scanlon Foundation Research Institute’s Mapping Social Cohesion results give cause for some cautious optimism about the trust Australians place in politicians and each other.

After more than a decade of downward slide, trust in federal government turned around during the pandemic, when Australians got behind political leaders and the COVID-19 response. And while the very high levels of trust during the ‘crisis phase’ were never likely to last, it is at least promising that in 2022 trust levels were still above the long-run average.

But history tells us that this trust is fragile and must be nurtured by political leaders. That means politicians who promise integrity and transparency must deliver on those promises. And governments should avoid setting unrealistic expectations about what they can achieve. Ultimately, trust is the political capital that our leaders draw on to make hard policy decisions. And building this capital is crucial for supporting the necessary actions on big, but slow-moving, challenges such as climate change and population ageing.

Similarly, the trust Australians have in other people, while down from 2020 highs, remains above where it was pre-COVID.

Even after taking account of socio-economic and demographic differences, those with higher trust in government and in other people were more likely to participate in community activities such as social, religious, and sporting groups, or volunteer organisations. That’s a powerful finding. It reinforces the importance of community engagement to people’s wellbeing.

On the other hand, the much lower levels of interpersonal trust among those with lower levels of education, or who live in disadvantaged neighbourhoods or consider themselves poor, reminds us of the broader social impacts of failing to address poverty in our communities.

One positive political development in 2023 has been the recognition of the importance of trust and civic engagement in building social cohesion. The Federal Government’s Measuring What Matters statement includes measures of trust in government, public services, and other people, as well as social connection, in its measures of social cohesion.

The focus on these indicators – as part of a suite of 50 measures to track the wellbeing of Australians – will hopefully generate increasing interest in these issues from politicians and the community.